Art Institute of Chicago

| Art Institute of Chicago | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Established | 1879; in present location since 1893 |

| Location | 111 South Michigan Avenue Chicago, USA |

| Visitor figures |

1,846,889 (2009)[1]

|

| Director | James Cuno |

| Website | www.artic.edu/aic |

The Art Institute of Chicago (AIC) is an encyclopedic fine art museum[2] located in Chicago, Illinois's Grant Park. The Art Institute has one of the world's most notable collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art in its permanent collection. Its diverse holdings also include significant Old Master works, American art, European and American decorative arts, Asian art and modern and contemporary art. It is located at 111 South Michigan Avenue in the Chicago Landmark Historic Michigan Boulevard District. The museum is associated with the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and is overseen by Director and President James Cuno. At one million square feet, it is the second largest art museum in the United States behind only the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.[3]

Contents |

History

In 1866, a group of 35 artists founded the Chicago Academy of Design in a studio on Dearborn Street, with the intent to run a free school with its own art gallery. The organization was modeled after European art academies, such as the Royal Academy, with Academians and Associate Academians. The Academy's charter was granted in March 1867.

Classes started in 1868, meeting every day at a cost of $10 per month. The Academy's success enabled it to build a new home for the school, a five story stone building on 66 West Adams Street, which opened on November 22, 1870.

When the Great Chicago Fire destroyed the building in 1871 the Academy was thrown into debt. Attempts to continue despite of the loss, using rented facilities, failed. By 1878, the Academy was $10,000 in debt. Members tried to rescue the ailing institution by making deals with local businessmen, before some finally abandoned it in 1879 to found a new organization, named the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts. When the Chicago Academy of Design went bankrupt the same year, the new Chicago Academy of Fine Arts bought its assets at auction.

In 1882, the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts changed its name to the current Art Institute of Chicago The same year, they purchased a lot on the corner of Michigan Avenue and Van Buren Avenue for $45,000. The property's building was leased, and a new building was constructed behind it to house the school's facilities.

With the announcement of the World's Columbian Exposition to be held in 1892–93, the Art Institute pressed for a building on the lakefront to be constructed for the fair, but to be used by the Institute afterwards. The city agreed, and the building was completed in time for the second year of the fair. Construction costs were paid by selling the Michigan/Van Buren property. On October 31, 1893, the Institute moved into the new building. From the 1900s to the 1960s the school offered with the Logan Family (members of the board) the Logan Medal of the arts, an award which became one of the most distinguished awards presented to artists in the US.

Between 1959 and 1970, the Institute was a key site in the battle to gain art & documentary photography a place in galleries, under curator Hugh Edwards and his assistants.

As Director of the museum starting in the early 1980s, James N. Wood conducted a major expansion of its collection and oversaw a major renovation and expansion project for its facilities. As "one of the most respected museum leaders in the country", as described by The New York Times, Wood created major exhibitions of works by Paul Gauguin, Claude Monet and Vincent Van Gogh that set records for attendance at the museum. He retired from the museum in 2004.[4]

In 2006, the Art Institute began construction of "The Modern Wing", an addition situated on the southwest corner of Columbus and Monroe. The project, designed by Pritzker Prize winning architect Renzo Piano, was completed and officially opened to the public on May 16, 2009. The 264,000 square-foot building makes the Art Institute the second largest art museum in the United States. The building houses the museum’s world-renowned collections of 20th- and 21st-century art, specifically modern European painting and sculpture, contemporary art, architecture and design, and photography.

The Museum’s Collection

The collection of the Art Institute of Chicago encompasses more than 5,000 years of human expression from cultures around the world and contains more than 260,000 works of art. The art institute holds works of art ranging from as early as the Japanese prints to the most updated American art.

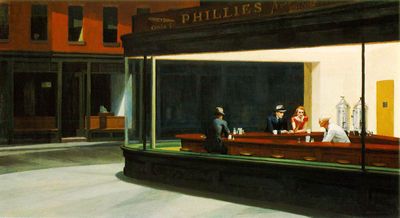

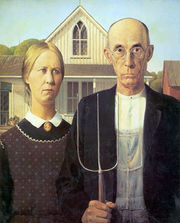

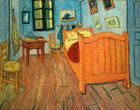

Today, the museum is most famous for its collections of Impressionist, Post-Impressionist, and American paintings. Included in the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection are more than 30 paintings by Claude Monet including six of his Haystacks and a number of Water Lilies. Also in the collection are important works by Pierre-Auguste Renoir such as Two Sisters (On the Terrace) and Henri Matisse's The Bathers, Paul Cézanne's The Basket of Apples, and Madame Cézanne in a Yellow Chair. At the Moulin Rouge by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec is another highlight, as are Georges Seurat's Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte and Gustave Caillebotte's Paris Street; Rainy Day. Non-French paintings of the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist collection include Vincent Van Gogh's Bedroom in Arles and Self-portrait, 1887. Among the most important works of the American collection are Grant Wood's American Gothic, Edward Hopper's Nighthawks and Mary Cassatt's The Child's Bath.

In addition to paintings, the Art Institute offers a number of other works. Located on the lower level are the Thorne Miniature Rooms which 1:12 scale interiors showcasing American, European and Asian architectural and furniture styles from the Middle Ages to the 1930s (when the rooms were constructed).[5] Another special feature of the museum is the Touch Gallery which is specially designed for the visually impaired. It features several works which museum guests are encouraged to experience though the sense of touch instead of through sight as well as specially designed description plates written in braille.[6] The American Decorative Arts galleries contain furniture pieces designed by Frank Lloyd Wright and Charles and Ray Eames. The Ancient Egyptian, Greek, and Roman galleries hold the mummy and mummy case of Paankhenamun, as well as several gold and silver coins.

The Terra Collection

Since April 2005, approximately fifty paintings originally from the Terra Museum (now the Terra Foundation) collection have been on loan to the Department of American Art at the Art Institute of Chicago. The collections of the Terra and the Art Institute are located in a new suite of galleries, and together provide one of the nation’s most comprehensive presentations of American art. The foundation’s collection of American works on paper are housed in the Department of Prints and Drawings at the Art Institute.

African American Art Collection

Institutions like the Art Institute of Chicago have assisted in creating a place for African American art to be explored freely without the restraints that once accompanied it. The pieces included in the Art Institute of Chicago’s African American art collection provide a historical illustration of the progress made by African Americans as well as their continuing struggle.

Specific pieces in this section of the museum give insight into the racial boundaries that existed in the past. Samuel J. Miller’s Frederick Douglass daguerreotype is an example of the way some African Americans managed to break away from stereotypes. The daguerreotype had been used by people like Louis Agassiz to show a “type” for ethnic groups. The style of J.T. Zealy’s daguerreotype photographs made the subject seem vulnerable, even animalistic. For example, “Delia,” (1850) shows a female slave completely exposed and in a sense victimized by the camera. Conversely, the Douglass daguerreotype shows a well-dressed man with a strong expression. This is the complete opposite from the submissiveness of the slaves in the Zealy photos. Douglass represented a new kind of Negro. He was educated and well-respected. This marks a shift in the idea of blackness and the way it is represented.

An artist that took it upon himself to continue to change the way blacks were in portrayed in art is Archibald J. Motley, Jr. He aimed to paint “his people” just as they were. Motley said he “wanted to instill a sense of racial pride into his work [7]. Motley attended the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and had to deal with occasional harassment from white classmates. Yet, he continued to believe that art was the best way to approach racial tensions [8].

In his piece “The Octoroon Girl,” (1925) Motley challenges the conventional image of an African American. While the woman in the painting fits the mold of “whiteness,” she actually is 1/8 black. Breaking away from the traditional views of blacks was indicative of the time period. References such as octoroon or mulatto were used to describe how much “black blood” a person possessed. Motley takes this concept from a negative connotation to one that is independent of social status.

Another piece included in the Art Institute of Chicago’s African American art collection is “The Boxer” by Richmond Barthe. Barthe is a significant figure among African American artists because his work was widely exhibited and recognized by reputable organizations. His sculptures depicted African Americans but were sought after pieces in the mainstream art world. In 1942, “The Boxer” coincided with a time period where black boxers like Joe Louis were fighting white opponents and actually beating them. This signified a big step for African Americans and equality, at least in the ring.

The changing idea of blackness and African American art was also advanced by artists like Jacob Lawrence. Most of his work focused on African American history and utilized techniques like repetition to emphasize his message. In “Graduation,” 1948, Lawrence addresses the importance of getting a diploma and how the event can affect a family’s morale. This piece went along with Langston Hughe’s poem by the same title [9] . The contrast of black and white in the painting can indicate the fact that such an event is significant to both African and white Americans. An emphasis on education has been central to African American advancement. Frederick Douglas was a major supporter of the idea that education was the path to social equality. “Graduation” manages to depict blacks as academically oriented, a positive image of African Americans.

The use of art as political motivators has been a key factor in African American art. The Art Institute’s collection also touches on the social implications of African American art. Black artists are a result of the fight their ancestors faced and the current boundaries that are still left to cross [10]. This powerful medium has evoked discussion about racial tensions and brought attentions that would have otherwise gone under the radar. Such approaches coincided with the emergence of political groups such as the NAACP and Africobra, for artists. African American artists utilized their work to address social and political issues of black people [11]. The combination of forces led to a more prevalent public conversation about racial equality. As African American artists banded together for projects such as the Wall of Respect, their concerns came to the forefront. Their paintbrushes had power.

In essence, the Art Institute of Chicago provides an accurate historical narrative of the lives of African Americans. Comparing daguerreotype images to the more recent pieces show a world of difference. Not only has the perception of African Americans changed, but also African American artists have established a separate school of art. The shift from being defined by African influence, to simply learning from the African link, has helped these artists break the mold they were previously forced to fit.

The Art Institute Building

The current building at 111 South Michigan Avenue is third address for the Art Institute. It was designed in the Beaux-Arts style by Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge of Boston, Massachusetts[12] for the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition as the World's Congress Auxiliary Building with the intent that the Art Institute occupy the space after the fair closed.

The Art Institute's famous western entrance on Michigan Avenue is guarded by two bronze lion statues created by Edward L. Kemeys. The sculptor gave them unofficial names: the south lion is "stands in an attitude of defiance," and the north lion is "on the prowl." When a Chicago sports team plays in the championships of their respective league (i.e. the Super Bowl or Stanley Cup Finals, not the entire playoffs), the lions are frequently dressed in that team's uniform. Evergreen wreaths are placed around their necks during the Christmas season.

The east entrance of the museum is marked by the stone arch entrance to the old Chicago Stock Exchange. Designed by Louis Sullivan in 1894, the Exchange was torn down in 1972, but salvaged portions of the original trading room were brought to the Art Institute and reconstructed.

The Art Institute building has the unusual property of straddling open-air railroad tracks. Two stories of gallery space connect the east and west buildings while the Metra Electric and South Shore lines operate below. The lower level of gallery space was formerly the windowless Gunsaulus hall, but is now home to the Alsdorf Galleries showcasing Indian, Southeast Asian and Himalayan Art. During renovation, windows facing north toward Millennium Park were added. The gallery space was designed by Renzo Piano in conjunction with his design of the Modern Wing and features the same window screening used there to protect the art from direct sunlight. The upper level formerly held the modern European galleries, but was renovated in 2008 and now features the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist galleries.

Libraries

Located on the ground floor of the museum is the Ryerson & Burnham Libraries. The Libraries' collections cover all periods of art, but is most known for its extensive collection of 18th-20th century architecture. It serves the museum staff, college and university students, and is also open to the general public. The Friends of the Libraries, a support group for the Libraries, offers events and special tours for its members.

Modern Wing

On May 16, 2009, the Art Institute opened the Modern Wing, the largest expansion in the museum's history [13]. The 264,000 square foot addition, designed by Renzo Piano, makes the Art Institute the second-largest museum in the US.[3] The Modern Wing is home to the museum's collection of early 20th-century European art, including Pablo Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, Henri Matisse’s Bathers by a River, and René Magritte’s Time Transfixed. It also houses contemporary art from after 1960; new photography, video media, architecture and design galleries; temporary exhibition space; shops and classrooms; a cafe and a restaurant, Terzo Piano, that overlooks Millennium Park from its terrace.[14] In addition, the Nichols Bridgeway connects a sculpture garden on the roof of the new wing with the adjacent Millennium Park to the north and a courtyard designed by Gustafson Guthrie Nichol.

In 2009, the Modern Wing won a Chicago Innovation Awards.[15]

Notable selections from the collection

_by_El_Greco_-_Chicago.jpg) El Greco, Saint Martin and the Beggar, c. 1597-1600 |

.jpg) Antoine Watteau, Fête champêtre (Pastoral Gathering), 1718-1721 |

Édouard Manet, Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers, 1864-1865 |

Édouard Manet, Seascape Calm Weather, 1864-1865 |

Gustave Caillebotte, Paris Street; Rainy Day, 1876-1877 |

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, By the Water, 1880 |

Pierre-Auguste Renoir, On the Terrace, 1881 |

Paul Cézanne, The Bay of Marseilles, view from L'Estaque,1885 |

Vincent Van Gogh, Self-portrait, 1887 |

Vincent Van Gogh, Bedroom in Arles, 1888 |

,_1890-91_(190_Kb);_Oil_on_canvas,_60_x_100_cm_(23_5-8_x_39_3-8_in),_The_Art_Institute_of_Chicago.jpg) Claude Monet, Wheatstacks (End of Summer), 1890-1891 |

Paul Cézanne, The Basket of Apples, c.1890s |

Paul Gauguin, Why are you angry? (No te aha oe Riri), 1896 |

Edgar Degas, Woman at Her Toilette, c. 1900-1905 |

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1906 |

Juan Gris, Portrait of Picasso, 1912 |

See also

- Looptopia

- Visual arts of Chicago

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sunday_Afternoon_on_the_Island_of_La_Grande_Jatte

External links

- The Art Institute of Chicago

- The Art Institute of Chicago: collections

- The Art Institute of Chicago: Inside-Out Antique & Collectable Postcard Exhibit - at The Chicago Postcard Museum

- The Ryerson and Burnham Libraries

- The Terra Foundation For American Art

- A Visitor's Experience: The Art Institute of Chicago

References

- ↑ "Exhibition and museum attendance figures 2009". London: The Art Newspaper. April 2010. http://www.theartnewspaper.com/attfig/attfig09.pdf. Retrieved 20 May 2010.

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/79.html

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 The New York Times

- ↑ Kennedy, Randy. "James N. Wood, President of the Getty Trust, Dies at 69", The New York Times, June 14, 2010. Accessed June 21, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.artic.edu/aic/collections/thorne

- ↑ http://www.artic.edu/aic/exhibitions/touch.html

- ↑ Rossen, Susan F., ed. Selections from The Art Institute of Chicago: African Americans in Art. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1999.

- ↑ Rossen, Susan F., ed. Selections from The Art Institute of Chicago: African Americans in Art. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1999. page 27

- ↑ Rossen, Susan F., ed. Selections from The Art Institute of Chicago: African Americans in Art. Chicago: The Art Institute of Chicago, 1999. 66.

- ↑ Parker, Daniel Texidor. African Art: The Diaspora and Beyond. Chicago: Daniel Texidor Parker, 2004. pg. 61.

- ↑ The Art of Culture: Evolution of Visual Arts by African American Artists, the Last Fifty Years. Chicago, IL: Africa International House USA, 2003. pg. 18.

- ↑ "1879-1913: The Formative Years". The Art Institute of Chicago. 2007. http://www.artic.edu/aic/aboutus/wip/formative/index.html. Retrieved 2007-06-20.

- ↑ The New York Times

- ↑ "A New Kind of Institutional Dining". Zagat.com. May 27, 2009. http://www.zagat.com/Blog/Detail.aspx?SCID=42&BLGID=20948.

- ↑ "2009 Chicago Innovation Award winners". Chicago Innovation Awards. http://www.chicagoinnovationawards.com/past-winners/2009.

|

|||||||||||